13 Profit under Rivalry

Up to this point, profit depended on three things:

- Your price

- Your demand

- Your costs

You could estimate demand.

You could discipline cost.

You could study sensitivity.

You could stage commitment.

Even under uncertainty, the structure was stable.

Now we introduce something different. A rival who also optimizes.

13.1 Profit Is No Longer a Curve

Previously, profit looked like this:

\[ \mathsf{\pi(P)} = \mathsf{(P - c)Q- f} \]

You chose a price.

Customers responded with their demand.

You optimized.

Now profit looks like this:

\[ \mathsf{\pi_i(P_i, P_j)} \]

Your profit depends on your price (\(\mathsf{P_i}\)) and your rival’s price (\(\mathsf{P_j}\)).

Your demand is no longer stable. It is conditional.

If your rival lowers price, your demand shifts.

If they raise price, your demand shifts.

If they enter your market, your demand splits.

Your profit curve is no longer a curve.

It is a moving surface.

13.2 From Curve to Surface

In earlier chapters, profit was a curve: profit as a function of your price.

When we add a rival, your profit depends on two prices:

The rival chooses a price.

You choose a price.

And each of you can adjust in response.

Profit is no longer a single curve you optimize in isolation. It becomes a surface: \(\mathsf{\pi(P_i, P_j)}\).

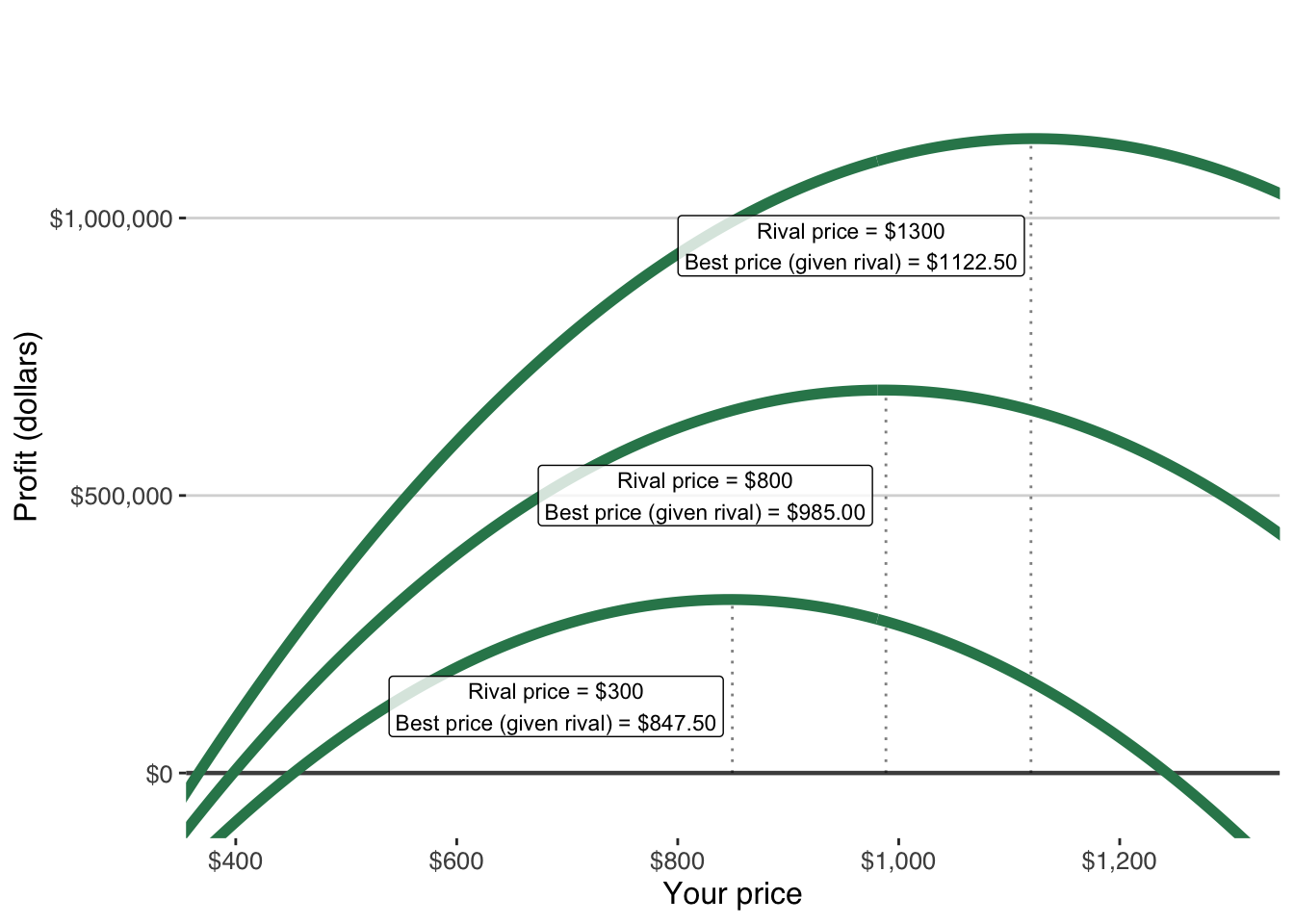

First, we hold the rival’s price fixed and look at a few slices of that surface.

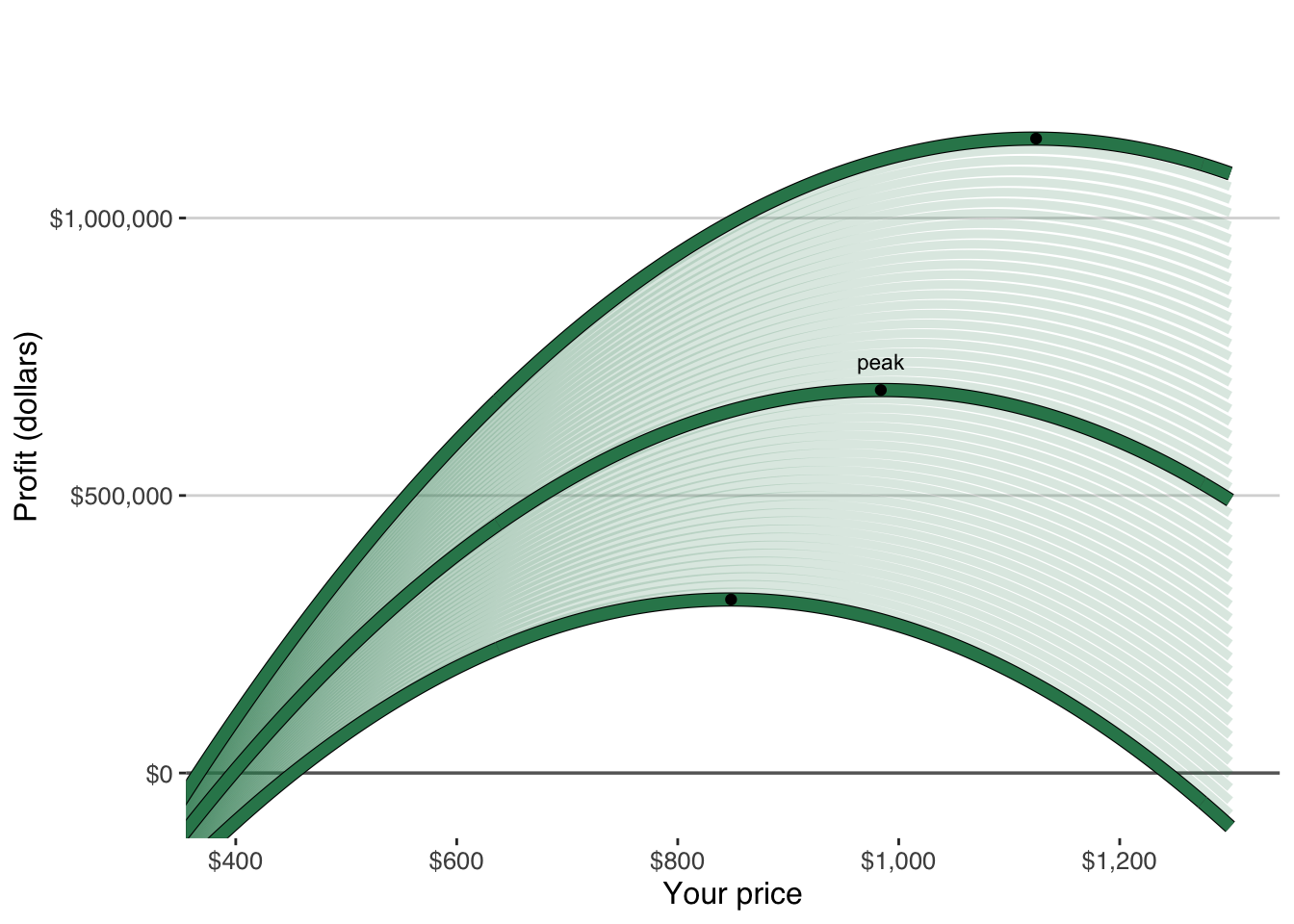

Next we fill in many more slices, revealing the surface.

Then we fill in many more slices. The faint curves show profit across many possible rival prices, and the highlighted points mark the peak of each featured curve (your best price given that rival price).

Profit is still profit reasoning. But it is profit reasoning under response.

13.3 A New Source of Uncertainty

Earlier, uncertainty came from:

- Demand estimation

- Cost estimation

- Scaling assumptions

Now there is a new source:

Strategic responses of rivals.

The rival is not noise.

The rival is not random.

The rival is optimizing profit at the same time you are and this changes how feasibility must be evaluated.

13.4 The Entrepreneurial Mistake

Many founders calculate profit as if they were alone.

They:

- Estimate willingness-to-pay.

- Choose a price.

- Calculate margin.

- Project scale.

Then they conclude:

“This is worth doing.”

But they have evaluated profit at their preferred price — not at the price that survives competition.

Under rivalry, the relevant question is not:

What is my optimal price?

It is:

What price survives when others optimize too?

13.5 Feasibility Under Rivalry

A business that is feasible in isolation may be infeasible under competition.

A business that appears robust may become fragile when margins compress.

Fixed costs that were recoverable alone may become unrecoverable when demand splits.

Competition does not change the logic of profit.

It changes the constraints.

Everything you learned still applies:

- Contribution margin

- Fixed cost commitment

- Scaling discipline

- Sensitivity

But now they must be evaluated at a competitive outcome.

13.6 The Decision Lens

From this chapter forward, profit must always be asked in this form:

Is this worth doing given that others will respond?

If your profit only exists when competitors remain passive, you do not have a business. You have a temporary condition.

Competition is not a separate topic from profit reasoning.

It is profit reasoning under intelligent response.

And that changes everything.