5 What Demand Is (and Is Not)

Entrepreneurs talk about demand constantly.

“We have strong demand.”

“There’s no demand for that.”

“Demand really took off after launch.”

Most of the time, what people mean by demand is some mix of interest, usage, adoption, or revenue. Those concepts are related, but they are not the same thing—and confusing them leads to bad decisions.

This chapter defines what demand actually is, what it is not, and how to recognize it when you see it. We are not estimating demand yet. We are not optimizing anything yet. We are simply getting clear about the object we are trying to learn.

5.1 Why Demand Comes First

Demand is the foundation for almost every downstream decision an entrepreneur cares about:

- pricing

- scaling

- cost structure

- investment

- competition

Without a clear sense of demand, these decisions become guesswork. With demand, they become disciplined judgment calls.

That is why this book treats demand as something to be learned deliberately, before worrying about sales tactics or growth strategies.

5.2 What Demand Is

Demand is a relationship between price and quantity.

Not a single number.

Not a forecast.

Not a time series.

A demand curve answers a very specific question:

At each possible price, how many units would customers buy?

Implicit in this question are two choices that matter later: what counts as one unit, and over what time frame the decision is made.

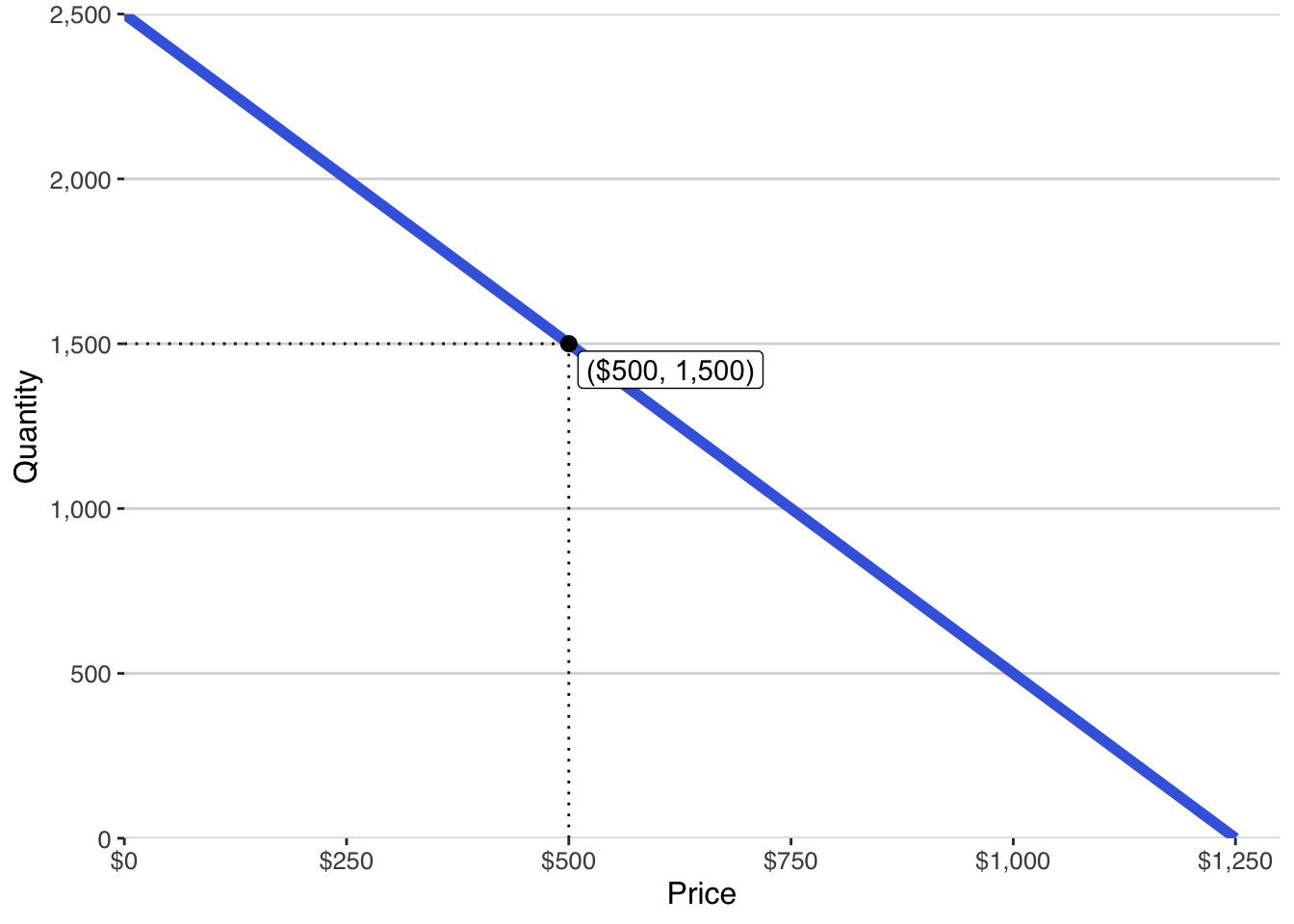

Figure 5.1 shows a simple demand curve.

The horizontal axis represents price.

The vertical axis represents quantity.

Each point on the curve answers a hypothetical question:

If the price were this, how much would be purchased?

For the demand curve plotted above, if price is $500, quantity is 1,500 units sold.

A few important things to notice immediately:

- Demand is about variation, not outcomes

- The curve summarizes many possible worlds, not one

- The curve itself is unknown—it must be inferred from evidence

This last point is crucial. Entrepreneurs do not choose a demand curve. They try to learn it.

5.3 How to Read a Demand Curve (Once)

For readers without economics training, it helps to be explicit—once—about what this picture does and does not mean.

A demand curve is not:

- a timeline

- a forecast of what will happen

- a strategy

- something you can “optimize” directly

Instead, think of it as a map.

Price is not shown as a cause in the usual sense. Moving along the curve does not mean time is passing or that a decision has been made. It simply shows how quantity would change if the price were different.

Later in the book, we will use demand curves to reason about pricing and profit. For now, the only job of the curve is to represent what customers are willing to do at different prices.

5.4 What Demand Is Not

Because demand is so central, it is easy to mistake other concepts for it. Let’s be explicit about a few common confusions.

Demand vs. Interest

Interest answers questions like:

- “Would you try this?”

- “Do you like the idea?”

Demand requires a price. Without price, there is no demand—only curiosity.

Demand vs. Adoption

Adoption tells you who has started using a product. Demand tells you how many would buy at different prices. Adoption is an outcome. Demand is a relationship.

Demand vs. Usage

Usage measures how much people actually consume after buying. Demand is about what they would choose before buying, under different prices.

Demand vs. Revenue

Revenue multiplies price by quantity. Demand explains how quantity responds to price. Mixing these up often leads entrepreneurs to chase revenue patterns without a clear understanding of the behavior underneath.

5.5 Changes Along a Curve vs. Changes in the Curve

One final visual distinction is worth seeing early, even if we do not dwell on terminology.

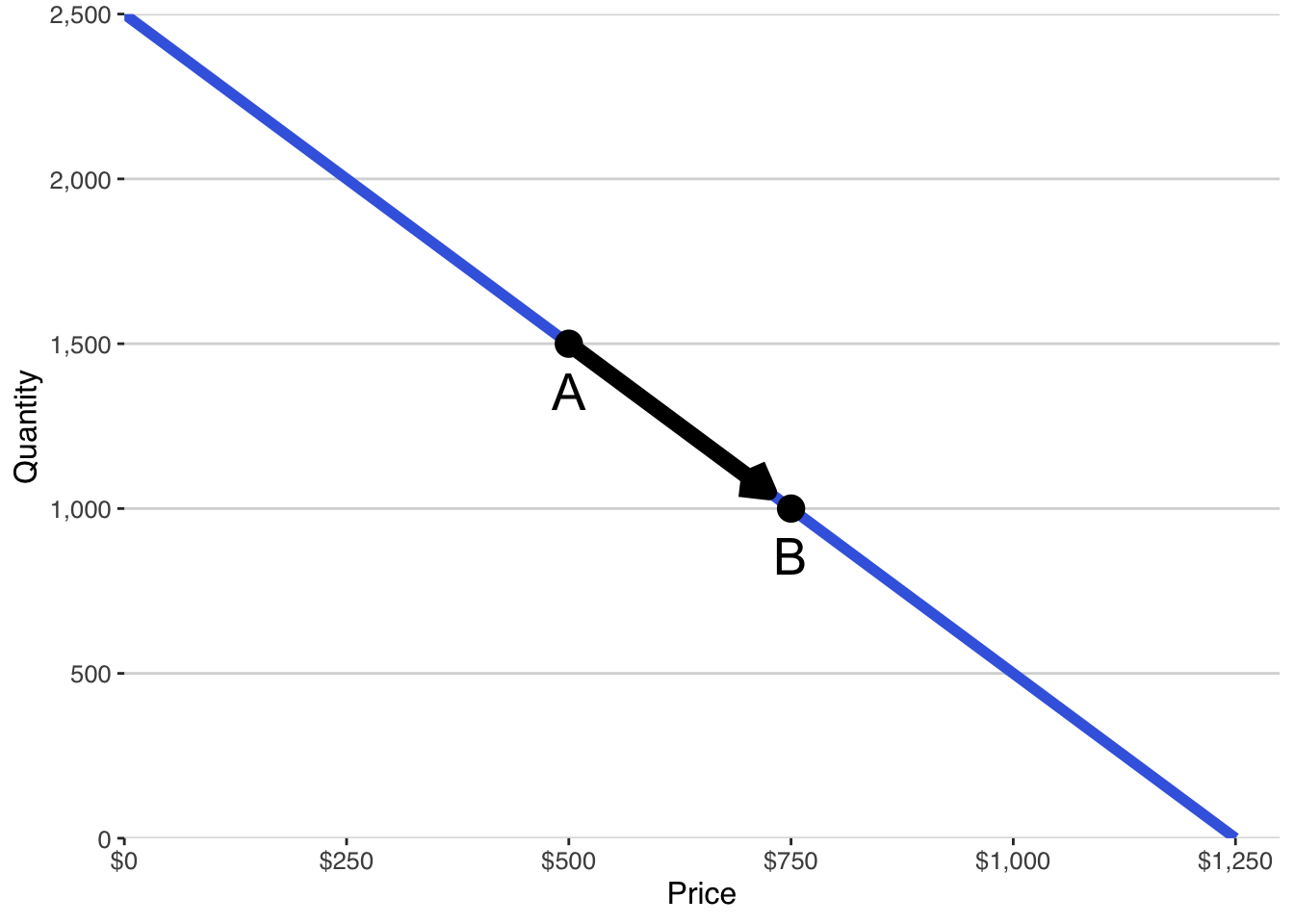

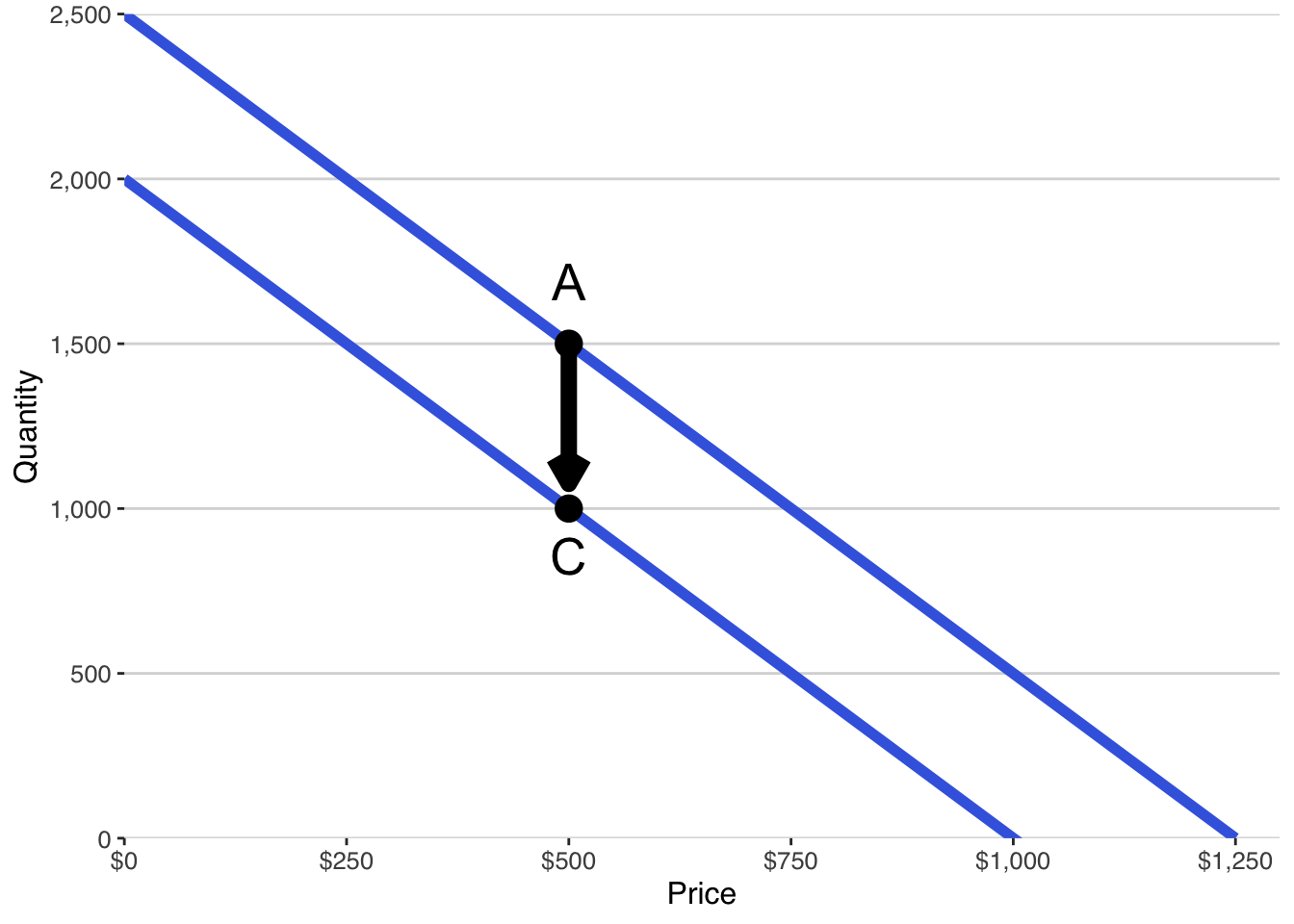

Figure 5.2 and Figure 5.3 show two different situations.

In the first case, outcomes change because the price changes.

In the second case, outcomes change because customers are different.

We will not spend time on traditional economics labels for this distinction. What matters for entrepreneurs is simply recognizing that:

- Sometimes results change because you changed the price

- Sometimes they change because demand itself is different

Learning demand means figuring out which situation you are in.

5.6 Where Demand Curves Come From (Preview)

Demand curves do not appear automatically. They are constructed from evidence.

In the next chapters, we will cover:

- how to design experiments that generate demand evidence

- how survey questions shape what can be learned

- how raw responses are transformed into price–quantity data

- how models turn that data into usable demand curves

For now, the goal is simpler: when you see a demand curve, you should know what kind of object it is—and what kind of work it can and cannot do.

Only then does it make sense to learn how to build one.