21 Strategic Commitment

21.1 Shaping the Game Before You Play It

Simultaneous and sequential games teach us how to make the best move in existing games. Strategic commitment goes beyond this—it is about changing the structure of the game itself, influencing competitors’ future choices before they act. In contrast to strategic flexibility, which allows firms to adjust their strategies in response to competitors, strategic commitment relies on long-term, irreversible decisions that signal strength, deters competitors, and influences market dynamics.

To understand strategic commitment, consider an ancient military commander landing on enemy shores. Instead of keeping his fleet ready for retreat, he burns his ships. The message to his troops is clear: there is no turning back, win or perish. This act transforms the strategic landscape. His soldiers fight with a new level of commitment, and the enemy, recognizing their desperation, may lose confidence. The same logic applies in business—companies can make strategic decisions that shape competitor behavior, customer expectations, and even regulatory landscapes.

At its core, strategic commitment is about creating and reinforcing competitive advantages. These commitments can take many forms:

- Investing in large-scale production to lower costs and deter entrants.

- Building strong brand loyalty that makes switching difficult for customers.

- Locking in exclusive supplier contracts that limit competitors’ access to key resources.

- Making public, irreversible promises to shape industry expectations.

Strategic commitment is not about making random, costly decisions. It’s about making deliberate, visible, and credible investments that make competitors hesitate and shift the game in your favor.

21.2 Credibility: The Key to Effective Commitment

A strategic commitment only works if competitors believe it. If the commitment is weak or easily reversible, competitors will simply ignore it and continue with their own best strategies. To be effective, a commitment must be:

- Visible – Competitors must clearly see and understand the commitment.

- Understandable – The logic behind the commitment must be apparent.

- Credible – The firm must not be able to back out of the commitment without severe consequences.

- Irreversible – The commitment should be costly or impossible to undo.

Consider Tesla’s investment in Gigafactories. By committing billions of dollars to battery production, Tesla signaled to competitors that it was locked into electric vehicles for the long term. This investment was both visible and irreversible, forcing other automakers to take Tesla seriously and rethink their strategies. Contrast this with companies that make vague announcements about “future electric vehicle ambitions” or plan to buy their batteries rather than make them—these are not commitments because they lack credibility.

Another classic example is Southwest Airlines’ fleet strategy. Southwest committed to using only Boeing 737 aircraft, which allowed the company to reduce maintenance costs, simplify training, and improve efficiency. Because this was a public and irreversible commitment, it sent a strong signal to competitors that Southwest had a durable cost advantage in the airline industry.

21.3 Types of Strategic Commitments

Strategic commitments come in many forms. Each type affects competitors, customers, and suppliers differently, shaping industry outcomes in unique ways.

1. Capacity Expansion

When a firm commits to increasing production capacity, it signals to competitors that price competition may not be worth it. If a new entrant knows that an established firm can flood the market with low-cost products, they may hesitate to enter.

Example: Amazon invested billions in massive fulfillment centers allowed it to offer faster delivery at lower costs, making it harder for smaller competitors to keep up. The investment signaled to competitors that it was committed to cost leadership and fast delivery and the commitment was credible because investment was large and largely irreversible.

2. Fixed Cost Investments

Companies that invest in expensive, industry-specific infrastructure can signal long-term commitment to a market. This discourages competitors who may be unsure about their own return on investment.

Example: Intel’s multi-billion-dollar semiconductor fabrication plants (fabs) require enormous upfront investment, making it nearly impossible for new entrants to compete without similar investments.

3. Product Positioning

A firm can commit to differentiating itself from competitors in a way that makes direct competition difficult. This often involves brand loyalty, unique technology, or niche market focus.

Example: Apple’s commitment to high-end, premium-priced devices signals that it is not interested in competing on price, forcing competitors to either match its quality or pursue budget-conscious consumers.

4. Contracts and Exclusivity

Exclusive agreements can lock in key suppliers or customers, making it difficult for competitors to operate efficiently.

Example: Microsoft’s multi-billion-dollar partnership with OpenAI ensured exclusive access to cutting-edge AI models, limiting competitors’ ability to use the same technology.

5. Regulatory and Political Commitments

Firms can shape industry regulations in ways that create barriers to entry. This may involve lobbying, standard-setting, or long-term compliance investments.

Example: Uber actively lobbied for regulations that favored ride-sharing platforms, ensuring its business model became legally entrenched in many cities.

Example: 1-800-Contacts could not legally implement its business model until lobbying removed regulation requiring contact lens sellers to also write the prescriptions.

21.4 Strategic Commitment in a Sequential Entry Game

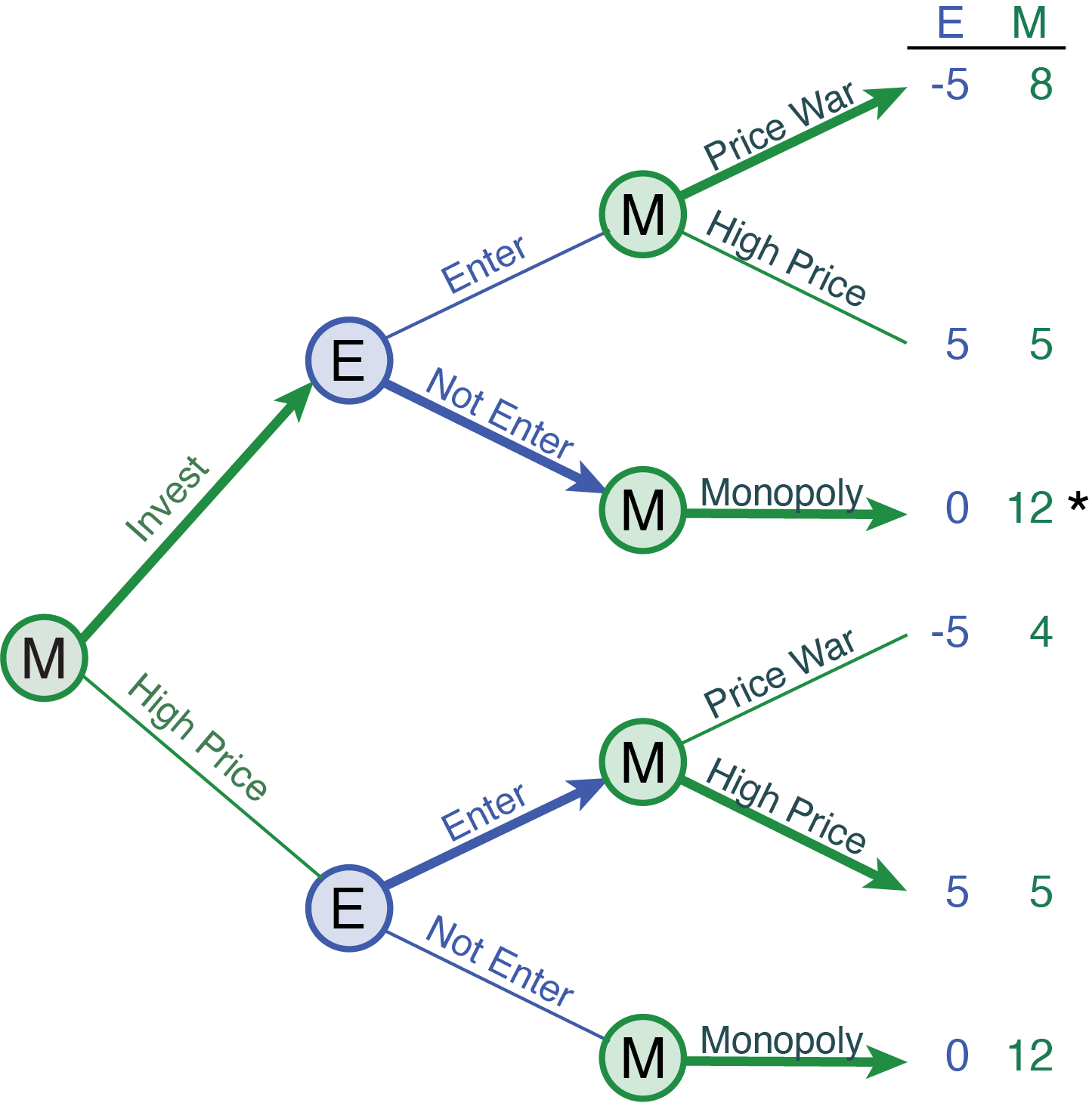

In our study of sequential games, we considered a monopolist facing a potential entrant. Initially, the monopolist’s threat to fight against entry seemed credible, but when we analyzed the game sequentially, the threat fell apart. The entrant recognized that the monopolist’s threat was not credible because its best response was to accommodate entry rather than engage in a costly price war. Enty occured and the monopolist accommodated as expected. This is a pretty lousy outcome for a monopolistic competitor who seemingly has the upper hand against the entrant.

Now, let’s introduce strategic commitment into the game. The monopolist, seeking to deter entry, can invest in moving down its learning curve—lowering variable costs to sustain aggressive pricing while maintaining profitability against future entrants that do not have the same efficiencies. This investment transforms the game. Before, the entrant could count on the monopolist accommodating. Now, the monopolist has credibly signaled that it can afford to fight, making entry less attractive.

The opportunity for the monopolist to invest in enhanced efficiency and lower costs adds another stage to the sequential entry game. Specifically, we add an earlier stage where the monopolist must decide whether to “invest” in strategic commitment by investing in efficiency and learning.

- If the monopolist does not invest, the game is unchanged;

- if it does invest, the monopolist can sustain lower prices in the future and the payoffs change.

After investment, the payoff of a price war increases from $4M to $8M. This new game, with its attempted strategic commitment, is constructed and solved in Figure 21.1.

As before, if the monopolist does not invest, a competitor will enter the market and both firms will split profits. However, if the monopolist invests in cost-cutting technology, the potential entrant may decide not to enter because competing would be unprofitable.

The game tree in extensive form reveals that the investment changes the equilibrium outcome:

- If the monopolist does not invest, the entrant enters and both firms make moderate profits.

- If the monopolist invests, the entrant stays out, and the monopolist keeps all profits.

By strategically committing to cost reduction, the monopolist effectively deters entry, reshaping the game in its favor.

21.5 When Strategic Commitment Backfires

Not all commitments succeed. Poorly designed commitments can trap firms into bad decisions or provoke competitors instead of deterring them.

1. The Sunk Cost Trap

Firms that commit too early or too heavily to a strategy may find themselves stuck with outdated technology or market positioning.

Example: Kodak’s commitment to film photography prevented it from embracing digital cameras early enough, leading to its decline. Example: Blackberry’s insistence on physical keyboards made it difficult to compete with touchscreen smartphones.

2. The Retaliation Risk

Sometimes, commitments provoke aggressive responses from competitors, leading to price wars or counter-commitments.

Example: Airlines that engage in price-matching commitments can find themselves in brutal fare wars, leading to losses instead of gains.

3. The Flexibility Problem

Commitments that lack built-in adaptability can become liabilities when market conditions change.

Example: Blackberry’s commitment to physical keyboards made sense at first, but when touchscreens became dominant, it struggled to pivot.

Example: Tesla’s commitment to battery production in its Gigafactories is difficult to adapt when overall demand for electric vehicles falls after many new entrants have entered.

21.6 Actionable Takeaways for Entrepreneurs

Strategic commitment is not just for large corporations—entrepreneurs can use these principles to shape markets, deter competitors, and strengthen positioning.

Before committing, ask:

- Is this investment visible, credible, and irreversible?

- How will competitors react? Does this commitment deter or provoke competition?

- Does this commitment give us a durable competitive advantage, or does it lock us into a fragile position?

- Can this commitment be leveraged for funding, partnerships, or market dominance?

In general, different competitive environments point to different opportunities for commitment:

- Commit to cost leadership early if scale is a feature of the prodution technology.

- Use branding and exclusivity for differentiation if customer needs are highly variable.

- Prioritize flexibility and avoid commitments that limit your ability to adapt to market changes when markets are uncertain and subject to frequent, rapid change.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to strategic commitment. As competitive environments differ based on their unique combination of customers, competitors, technologies, and suppliers. Any successful strategic commitment must target the specific peculiarities of the competitive environment.

21.7 Conclusion

Strategic commitment is literally a game-changing tool in competitive strategy. By making deliberate, irreversible moves, firms can shape industry dynamics, deter rivals, and secure profitability. However, commitment must be credible and strategic—poorly designed commitments can backfire. Beware of the inflexibility of commitments in highly uncertain and volatile markets.

Entrepreneurs should view commitment not as a gamble, but as a calculated move to reshape the playing field in their favor.