9 Cost

What You Choose, What You Commit

Once demand has been learned, the analysis can finally change.

Until now, the central uncertainty has been external: how customers respond to price. That uncertainty had to be learned from evidence rather than assumed.

Costs are different.

Costs are not revealed by the market in the same way demand is. They are largely the result of design choices and strategic commitments made by the firm.

This does not make costs trivial. It makes them decisional.

In this chapter, we bring costs back into the picture—not as accounting detail, but as the second pillar of pre-revenue profit reasoning. The goal is not to predict expenses with precision. It is to understand how different cost structures interact with demand to shape what is worth doing.

9.1 Why Cost Comes After Demand

Entrepreneurs often try to reason about costs early. This is understandable. Costs feel concrete, controllable, and familiar.

The problem is not that cost matters too little.

The problem is that it matters differently once demand is understood.

Before demand is learned, cost analysis tends to float. Variable costs are estimated without knowing how much will be sold. Fixed costs are debated without knowing whether any price can support them. Precision accumulates in spreadsheets, while the core uncertainty remains untouched.

Learning demand changes this.

Once demand is represented as a price–quantity relationship, cost questions become anchored. Some costs matter a great deal. Others matter hardly at all. Many decisions that previously felt open-ended become constrained.

This is why cost comes after demand in the logic of this book.

Demand tells you whether revenue is possible.

Cost tells you whether that revenue can support the commitments you are considering.

Only when both are present does the question “Is this worth doing?” become concrete in an economic sense.

The sections that follow separate costs into two broad categories—variable and fixed—not because accounting requires it, but because decision-making does.

9.2 Variable Costs: Costs That Scale with Demand

Once demand has been learned, the first cost question that matters is deceptively simple:

What does it cost to serve one more unit of demand?

This is the essence of variable cost.

Variable costs are costs that scale with quantity. They increase as more units are sold and decrease as fewer units are sold. In pre-revenue decisions, they are often easier to reason about than fixed costs—but also easier to misunderstand.

What “Variable” Really Means in Practice

In principle, a variable cost is any cost that changes with the number of units sold.

In practice, the relevant question is narrower:

If one additional customer buys one additional unit, what additional cost does the firm incur?

This framing matters because not all costs that feel “operational” are meaningfully variable at the margin. Some costs change only in steps. Others are fixed over wide ranges and then jump suddenly.

For early decision-making, the goal is not to classify every expense perfectly. It is to identify the costs that materially affect the feasibility of serving demand at different prices.

Examples of variable costs often include:

- materials or inputs consumed per unit,

- fulfillment, delivery, or transaction costs,

- usage-based fees paid to partners or platforms,

- incremental labor required per unit sold.

What matters is not accounting labels, but economic behavior.

Why Variable Cost Matters for Pricing Feasibility

Variable cost plays a special role because it sets a hard lower bound on viable pricing.

If the price charged does not exceed variable cost, selling more units makes the situation worse, not better. Demand may exist, but it is economically irrelevant.

This is why variable cost is the first cost to reintroduce after demand.

Demand curves tell you how quantity responds to price. Variable cost tells you which parts of that curve are even worth considering.

Before asking which price maximizes profit, the entrepreneur must first ask:

Which prices are even feasible given the cost of serving one more unit?

This question can often be answered approximately—and that is sometimes enough.

Estimating Variable Costs Before Revenue Exists

Like demand, variable costs cannot be measured before operations begin. But unlike demand, they are not primarily learned from customers.

They are learned from design choices, supplier terms, process assumptions, and benchmarks.

Early variable cost estimates should be treated as ranges, not point values.

The goal is not precision. It is discrimination:

- costs that are clearly low enough to support demand at plausible prices,

- costs that are clearly too high,

- and costs where small changes would materially affect the decision.

If variable cost uncertainty overwhelms demand uncertainty, that is a signal that the business model itself is underspecified.

Variable Costs Are Often Chosen, Not Given

One final caution is important.

Entrepreneurs sometimes treat variable cost as an external constraint—something imposed by technology or the market.

In reality, variable costs are often the result of design decisions:

- how the product is built,

- how it is delivered,

- what is outsourced versus internal,

- what quality level is targeted.

Different choices lead to different variable cost structures, even for the same demand.

This is why variable cost analysis is not about discovering the “true” cost. It is about understanding how cost choices interact with demand to shape what is worth doing.

Only after this interaction is understood does it make sense to ask whether fixed costs are justified.

9.3 Fixed Costs: Commitments, Not Expenses

If variable costs determine whether selling one more unit makes sense, fixed costs determine whether the venture itself makes sense.

Fixed costs are costs that do not change with the number of units sold—at least over the relevant range of decisions. They must be paid whether demand is high or low, or even if demand turns out to be zero.

Because of this, fixed costs are best understood not as expenses, but as commitments.

What Makes a Cost “Fixed” in Decision Terms

In accounting, fixed costs are often defined mechanically: costs that do not vary with output.

For decision-making, a more useful definition is this:

A fixed cost is a cost you incur because you decided to proceed, not because a customer chose to buy.

Examples commonly include:

- long-term leases or contracts,

- salaried labor that cannot be scaled down quickly,

- specialized equipment or infrastructure,

- platform or software commitments,

- upfront investments in brand, compliance, or systems.

What matters is not whether a cost is technically fixed forever, but whether it is difficult or costly to reverse once incurred.

Fixed Costs Raise the Bar for Demand

Fixed costs change the nature of the decision.

Once a fixed cost is incurred, the venture must generate enough contribution from demand to justify that commitment. This introduces a threshold effect that does not exist with variable costs alone.

Low fixed costs create flexibility:

- demand can be tested,

- pricing can be adjusted,

- the venture can be abandoned with limited loss.

High fixed costs reduce flexibility:

- demand must be large enough and reliable enough,

- pricing mistakes become more costly,

- early errors are harder to undo.

This is why fixed costs are often the real source of risk in pre-revenue decisions—not uncertainty about variable costs.

Timing Matters More Than Magnitude

Entrepreneurs often focus on how large fixed costs are.

Equally important is when they must be incurred.

Some fixed costs are required immediately. Others can be delayed until demand is better understood. Some can be staged or scaled.

From a decision perspective, this timing is critical.

Delaying fixed commitments preserves option value. It allows demand uncertainty to be reduced before irreversible choices are made.

This is why experienced entrepreneurs are often less concerned with minimizing fixed costs than with postponing them.

Fixed Costs Are Chosen, Not Discovered

Like variable costs, fixed costs are often treated as constraints imposed by the environment.

In reality, they are frequently the result of strategic choices:

- how fast to scale,

- what level of quality or capability to build,

- whether to own or rent,

- whether to automate or rely on manual processes.

Different choices imply different fixed cost structures—even with the same demand.

This means that fixed cost analysis is not about uncovering the “true” cost of a business. It is about understanding which commitments you are willing to make, given what you know about demand.

Only once that relationship is clear does it make sense to ask whether the expected rewards justify the commitments.

Before looking at cost structures graphically, it helps to name the relationship we’ve been describing.

For many entrepreneurial decisions, total cost can be written as:

\[ \mathsf{C(q)} = \mathsf{f + cq}\]

This is not a theory of cost. It is a way of separating two different kinds of commitment.

- \(\mathsf{C(q)}\) represents total cost as a function of output or sales.

- \(\mathsf{f}\) represents fixed cost — what you commit to before knowing how much you will sell.

- \(\mathsf{c}\) represents variable cost per unit — what you incur each time you produce or sell one more unit.

- \(\mathsf{q}\) is the level of output or sales.

This equation does not tell you what costs should be. It simply makes explicit what is already true: some costs depend on scale, and some do not.

Different cost structures are different choices of \(\mathsf{F}\) and \(\mathsf{c}\). Those choices determine how risky the business becomes as demand turns out higher or lower than expected.

9.4 Cost Structure Shapes Risk, Not Just Profit

At this point, it is tempting to think about cost only in terms of profit.

Lower costs mean higher profit. Higher costs mean lower profit. This framing is familiar—and incomplete.

Cost structure does more than shape expected profit. It shapes risk.

Two ventures can face the same demand and the same prices, and yet present very different decisions because their cost structures are different.

Same Demand, Different Risk

Consider two ways of serving the same demand:

- One relies on low fixed costs and higher variable costs.

- The other relies on high fixed costs and lower variable costs.

At first glance, the second option may look more attractive. If demand materializes, margins are higher and profits grow quickly.

But that upside comes with a condition: demand must be sufficiently large and sufficiently reliable.

High fixed costs concentrate risk. They make outcomes more sensitive to errors in demand estimation, pricing, or timing. If demand is weaker than expected, losses accumulate quickly.

Low fixed costs distribute risk. They reduce upside, but they also limit downside. Mistakes are survivable. Learning can continue.

This is why cost structure is not just a technical detail. It is a strategic choice about how much uncertainty you are willing to absorb.

Why Break-Even Is About Risk, Not Targets

Entrepreneurs often talk about “breaking even” as a milestone or goal.

In decision terms, break-even is something else entirely.

It is the point at which demand becomes sufficient to justify the fixed commitments that have been made.

Before that point, each unit sold may reduce losses, but the venture as a whole remains unsupported. After that point, additional demand begins to create surplus rather than simply covering commitments.

This is why fixed costs raise the stakes of demand learning. They do not just affect profitability; they determine how much demand must exist before the venture is viable at all.

Understanding this threshold matters more than predicting the exact level of profit.

Cost Structure Determines Which Errors Matter Most

Every early venture makes mistakes. What differs is which mistakes are fatal.

With low fixed costs, errors in demand estimation are often tolerable. Prices can be adjusted. Offerings can be refined. The venture can retreat or pivot.

With high fixed costs, the same errors can be decisive. There may be no room to wait, revise, or learn further. The venture must succeed quickly—or fail.

This is why experienced entrepreneurs often appear conservative about fixed commitments, even when they are optimistic about demand.

They are not pessimistic. They are managing risk.

Cost Choices as Part of the Decision

Seen this way, cost structure is not something to be optimized after the fact.

It is part of the decision itself.

Choosing a cost structure is choosing:

- how much uncertainty you can tolerate,

- how much learning you need before committing,

- and how much downside you are willing to accept if demand disappoints.

These choices cannot be evaluated independently of demand. They only make sense together.

In the next section, we turn to a final principle that ties this chapter together: why early cost analysis should remain deliberately coarse—and why more precision is not always better.

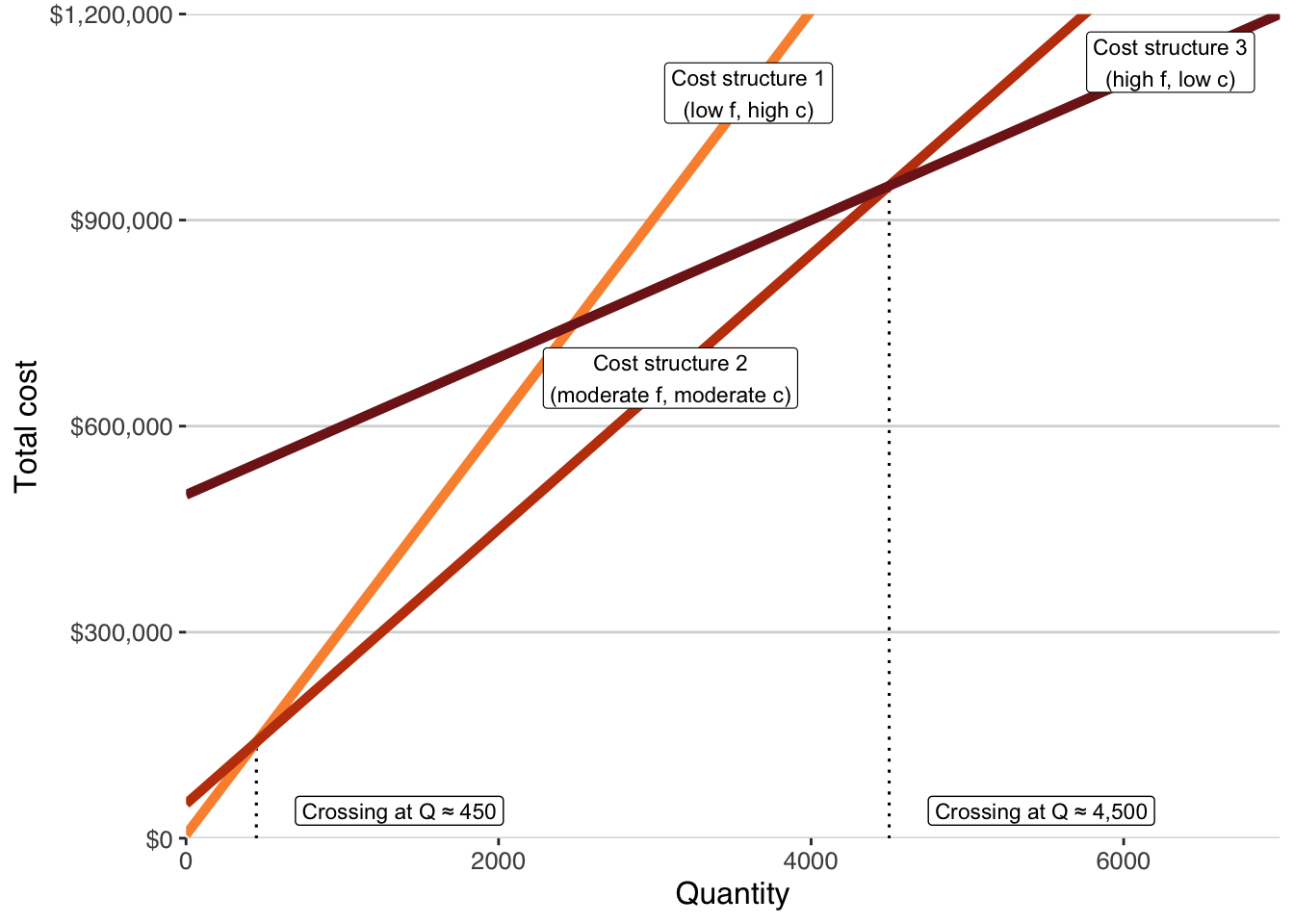

It helps to see how cost structure translates into risk.

In Figure 9.1, multiple ways of serving the same demand are shown. Each reflects a different commitment profile. Higher fixed costs only make sense if demand materializes at sufficient scale; until then, they increase downside exposure rather than efficiency.

A crossing point is not a goal. It is a condition. Choosing a high–fixed-cost structure is a bet that demand will reach and remain above this level. Choosing a low–fixed-cost structure preserves flexibility if it does not.

9.5 Break-Even Is a Constraint, Not a Target

One concept often introduced early in cost discussions is break-even.

Break-even answers a narrow but important question: how much must be sold for this cost structure not to lose money? It identifies the quantity at which revenue just covers fixed and variable costs.

That makes break-even a constraint, not a goal.

Reaching break-even does not mean a venture is attractive, scalable, or worth the risk it requires. It simply means losses stop increasing. A business that barely breaks even has not succeeded; it has only survived.

The entrepreneurial value of break-even analysis lies elsewhere. It clarifies how demanding a cost structure is. High fixed costs push the break-even quantity higher, increasing exposure to demand uncertainty. Low fixed costs lower the bar, but often at the expense of higher variable costs later.

Seen this way, break-even is not something to aim for. It is something to inspect.

It tells you what demand must exist before profit becomes possible—and therefore how fragile or robust the decision is given what you currently know about demand.

9.6 Why Cost Alone Cannot Decide Anything

It is tempting to treat cost analysis as decisive.

Lower costs feel safer. Leaner operations feel prudent. Reducing fixed commitments often feels like progress. But cost analysis by itself cannot answer the entrepreneurial question that matters most.

Cost does not create value. Cost does not generate demand. Cost does not determine whether customers will buy.

Cost only tells you what it takes to serve demand if it appears.

This is why cost reductions that ignore demand can be misleading. A lower-cost structure can still be the wrong choice if demand is small, price-sensitive, or uncertain. Conversely, a higher-cost structure can be the right choice if demand is strong enough to support it.

Cost narrows the space of viable decisions. It does not choose among them.

Until cost is considered together with demand, analysis remains incomplete. You may know what is cheaper—but not what is better.

9.7 Looking Ahead: Cost Inside the Profit Decision

At this point, the structure of the problem should be coming into focus.

Demand tells us what the market might do. Cost tells us what we must commit to serve it.

Neither is sufficient on its own.

The entrepreneurial decision is not about demand in isolation, and it is not about cost in isolation. It is about whether the combination of demand and cost can plausibly generate enough surplus to justify moving forward.

That question is a profit question.

Profit is where demand uncertainty and cost commitments meet. It is where pricing, scale, and structure interact. And it is where the original question—“Is this worth doing?”—finally becomes answerable in a disciplined way.

The next chapter brings these elements together. It shows how demand evidence and cost choices combine to evaluate profit before revenue exists—and how entrepreneurs can make that evaluation explicit rather than implicit.

Only then is it time to make the call.