10 Scale and Population

How Fixed Costs Force the Question

Once costs are understood as commitments, a new constraint appears.

Variable costs tell us which prices are feasible. Fixed costs tell us how much demand must exist before the venture can survive.

But fixed costs introduce a question that demand curves alone cannot answer:

Is there enough demand in the world—at the prices we can charge—to justify the commitments we are considering?

Up to this point, demand has been treated structurally. We have learned how quantity responds to price without yet asking how large the market is or how many customers might ultimately be reached.

That restraint was intentional.

Scale does not matter when no commitments have been made. It matters immediately once fixed costs are introduced.

Fixed costs force demand to be aggregated. They turn a price–quantity relationship into a question of reach, adoption, and population size. At that point, it is no longer enough to know how customers respond. We must also ask how many customers could plausibly be served.

This chapter introduces scale and population—not as marketing abstractions, but as decision constraints imposed by cost.

Only then can profit be evaluated honestly.

10.1 Entrepreneurs often talk about “market size” as if it were part of demand.

It is not.

Demand describes how customers respond to price. It answers questions like:

- How sensitive is quantity to price?

- Is demand steep or flat?

- Does lowering price meaningfully increase adoption?

Scale answers a different question:

- How many customers could possibly show up at all?

These are fundamentally different uncertainties.

A venture can face strong demand from a small population or weak demand from a large one. The shape of demand tells us nothing about how many people exist, how many can be reached, or how many would ever consider buying.

This distinction matters because fixed costs aggregate demand. They require not just willingness to pay, but enough people willing to pay.

Population Is a Constraint, Not an Estimate

Population size is often treated as something to be forecast.

That framing is misleading.

For entrepreneurial decision-making, population is better understood as a constraint:

- a ceiling on how much demand can ever materialize,

- a limit on how much contribution fixed costs can draw from,

- and a bound on how wrong optimistic projections can be.

Population does not tell you what will happen. It tells you what cannot happen.

This is why population enters profit reasoning only after cost structure is understood. Without fixed costs, population size is largely irrelevant. With fixed costs, it becomes decisive.

Reach Comes Before Adoption

Even when a population exists, it may not be reachable.

Before asking how many people will adopt, a more basic question must be answered:

Can these people realistically be reached at all?

Reach depends on:

- channels,

- geography,

- regulation,

- attention,

- trust,

- and cost of access.

A population that exists but cannot be reached is economically equivalent to one that does not exist.

This is why scale is not a marketing problem to be solved later. It is a feasibility condition that must be checked before commitments are made.

This Is Not TAM/SAM/SOM

Some entrepreneurs may be tempted to translate these questions into traditional market-sizing frameworks such as TAM, SAM, or SOM. Those tools are designed to approximate revenue potential in well-defined markets. The question here is different. We are not estimating market share or forecasting growth. We are asking whether a chosen cost structure could plausibly be supported by scaled demand at feasible prices. That question must be answered before competitive dynamics or market share can be meaningfully discussed.

Instead, we start with:

- learned demand,

- chosen costs,

- and imposed commitments.

Only then do we ask whether a sufficiently large, reachable population exists to support them.

Scale is not an aspiration here. It is a test.

If the required population size is implausible given what is known about reach and adoption, the decision should be reconsidered—regardless of how elegant the demand model looks.

10.2 Adoption Is Not Penetration

Once population enters the analysis, a second distinction becomes unavoidable.

Not everyone in a population will buy.

But not everyone who could buy needs to buy.

Entrepreneurs often blur these ideas together under phrases like “market share” or “capture rate.” That shortcut creates confusion precisely when clarity matters most.

To reason about scale responsibly, adoption and penetration must be separated.

Adoption Is a Customer-Level Decision

Adoption is about who says yes.

It reflects individual customer choices:

- whether the problem is salient,

- whether the solution fits,

- whether the price is acceptable,

- whether trust has been established.

Adoption is governed by demand.

It shows up in:

- the shape of the demand curve,

- price sensitivity,

- and willingness to pay.

When demand we considered demand earlier in the book in Chapter 5 and Chapter 8, adoption was already present implicitly. The customers who participated in demand experiments revealed how likely they were to buy at different prices.

What adoption does not tell us is how many such customers exist in the world.

Penetration Is an Aggregate Outcome

Penetration answers a different question:

What fraction of a population ultimately adopts?

This is not a single customer decision. It is the cumulative result of:

- awareness,

- access,

- timing,

- trust,

- substitutes,

- and competition.

Penetration cannot be observed in early experiments.

It cannot be directly estimated from small samples.

And it cannot be assumed without consequence.

Yet penetration is exactly what fixed costs require.

Fixed costs do not care who adopts.

They care how many do.

This is why penetration enters the analysis only after costs are understood. It is not part of demand learning. It is part of feasibility checking.

Why Early Demand Data Cannot Give You Penetration

A common mistake is to take early adoption signals and scale them up mechanically.

For example:

- “30% of interviewees said they would buy.”

- “Our pilot converted at 15%.”

- “Early users are very engaged.”

None of these imply a penetration rate.

Early adopters are not representative of the full population. They are often:

- more motivated,

- more informed,

- more tolerant of friction,

- and more forgiving of imperfection.

This does not make early data useless. It makes it local.

Demand experiments tell you how a type of customer responds to price.

They do not tell you how many such customers exist, or how broadly that response will generalize.

Confusing adoption with penetration is one of the fastest ways to underestimate risk.

Penetration Is Not a Goal — It Is a Requirement

Penetration is often framed aspirationally:

- “If we get just 5% of the market…”

- “We only need a small share…”

This framing hides the real issue.

Penetration is not something you aim for.

It is something your cost structure demands.

Given:

- a fixed cost,

- a variable cost,

- a feasible price range,

- and a population size,

there is a minimum penetration rate below which the venture cannot work at all.

That rate is not a forecast.

It is a constraint.

If the required penetration feels implausible given what is known about reach, trust, and customer behavior, the decision should be reconsidered—regardless of how exciting the idea feels.

Why This Is Still Not a Competition Question (Yet)

Penetration will eventually be shaped by competition.

But at this stage, we are not asking:

- who wins,

- who loses,

- or how share is divided.

We are asking a simpler, more prior question:

Is it plausible that enough people could ever adopt to support the commitments we are considering?

Only if the answer is yes does it make sense to move on to competitive dynamics later.

10.3 Market Existence Is Not Market Access

Up to this point, population has been treated abstractly: as a number of people who could, in principle, adopt.

That abstraction is useful—and dangerous.

A population can exist without being reachable.

And for entrepreneurial decision-making, unreachable demand is indistinguishable from nonexistent demand.

This is why market existence and market access must be separated.

Market Existence Answers “Who Is Out There?”

Market existence is about who could plausibly have the problem.

It defines the outer boundary of scale:

- who experiences the unmet need,

- who fits the use case,

- who could benefit from the solution.

This population may be large or small. It may be obvious or emerging. In some cases, it may not yet be named as a market at all.

At this stage, existence is a conceptual classification problem, not a forecasting exercise.

But existence alone is not enough.

Market Access Answers “Who Can Be Reached?”

Market access asks a more restrictive question:

Which of these people can actually be reached, engaged, and served?

Access depends on constraints that demand curves do not capture:

- whether the population can be identified,

- where they can be found,

- whether communication channels exist,

- whether trust can be established,

- whether legal, institutional, or cultural barriers apply.

A population that cannot be reached cannot generate demand, no matter how strong the need.

Access Is a Structural Constraint, Not a Marketing Problem

Entrepreneurs often treat access as something that can be solved later with better marketing, more effort, or more spend.

That framing is misleading.

Access is often shaped by structure:

- channel availability,

- platform rules,

- regulation,

- gatekeepers,

- switching costs,

- and social risk.

Some access barriers can be reduced with time and investment. Others cannot.

This is why access must be assessed before fixed costs are justified, not after.

Why Early Demand Experiments Do Not Guarantee Access

Early demand experiments are usually conducted with people who are:

- easy to find,

- willing to talk,

- already aware of the problem,

- and open to new solutions.

This is appropriate for learning demand.

It is not evidence of broad access.

Scaling from early demand to population demand requires more than rescaling a curve. It requires confidence that the same kinds of customers can be reached repeatedly, at reasonable cost, and without eroding trust or margins.

If access deteriorates as scale increases, penetration requirements become irrelevant—because the population cannot be activated in the first place.

Access Reduces the Effective Population

For decision-making, the relevant population is not the total number of people who might benefit.

It is the number who are:

- reachable,

- engageable,

- and realistically serviceable.

Access therefore shrinks population.

This is not a pessimistic adjustment. It is a realism filter.

Only accessible population should be used when evaluating whether fixed costs and pricing decisions can be supported.

Anything else is wishful thinking.

10.4 Required Scale Is a Consequence of Fixed Cost

At this point, the logic of scale should feel less mysterious—and less aspirational.

Scale is not something entrepreneurs choose because they want to grow.

It is something they inherit from the commitments they make.

Once fixed costs enter the picture, scale becomes a requirement.

Fixed Costs Imply a Minimum Viable Scale

Fixed costs must be supported by contribution from demand.

That contribution depends on:

- the price that can be charged,

- the variable cost of serving demand,

- and the quantity sold.

Taken together, these imply a minimum level of scaled demand below which the venture cannot work at all.

This minimum is not a target to aim for.

It is a boundary that must be crossed.

If demand never reaches this level, losses persist regardless of effort or efficiency. No amount of enthusiasm or execution can compensate for insufficient scale relative to commitment.

Scale Emerges from Structure, Not Ambition

Entrepreneurs often speak about scale as if it were a strategy.

In reality, scale is an implication.

Given:

- a chosen cost structure,

- a feasible price range,

- and an accessible population,

there is a range of quantities that make the decision viable—and a much larger range that do not.

Scaling does not make a bad structure good.

It only amplifies what is already there.

This is why scale belongs after cost in the logic of this book. Without fixed costs, scale barely matters. With fixed costs, it dominates everything else.

Required Scale Is Not a Forecast

It is tempting to treat required scale as a prediction:

- how many customers will buy,

- how fast adoption will occur,

- or what share of a market will be captured.

That temptation should be resisted.

Required scale is not a statement about what will happen.

It is a statement about what must happen for the decision to succeed.

It answers a conditional question:

If this venture is to work, how much demand must ultimately materialize?

That question is prior to forecasting, competition, or growth planning.

Why This Clarifies Risk

Once required scale is made explicit, risk becomes easier to reason about.

The question is no longer: “Is this a big market?”

It becomes: “Is it plausible that enough accessible customers will adopt, at feasible prices, to support the commitments we are considering?”

If the required scale feels fragile—dependent on optimistic assumptions about access, adoption, or timing—that fragility should be acknowledged explicitly.

Conversely, if the required scale is modest relative to the accessible population, the decision becomes more robust, even if uncertainty remains.

This is what disciplined entrepreneurial judgment looks like.

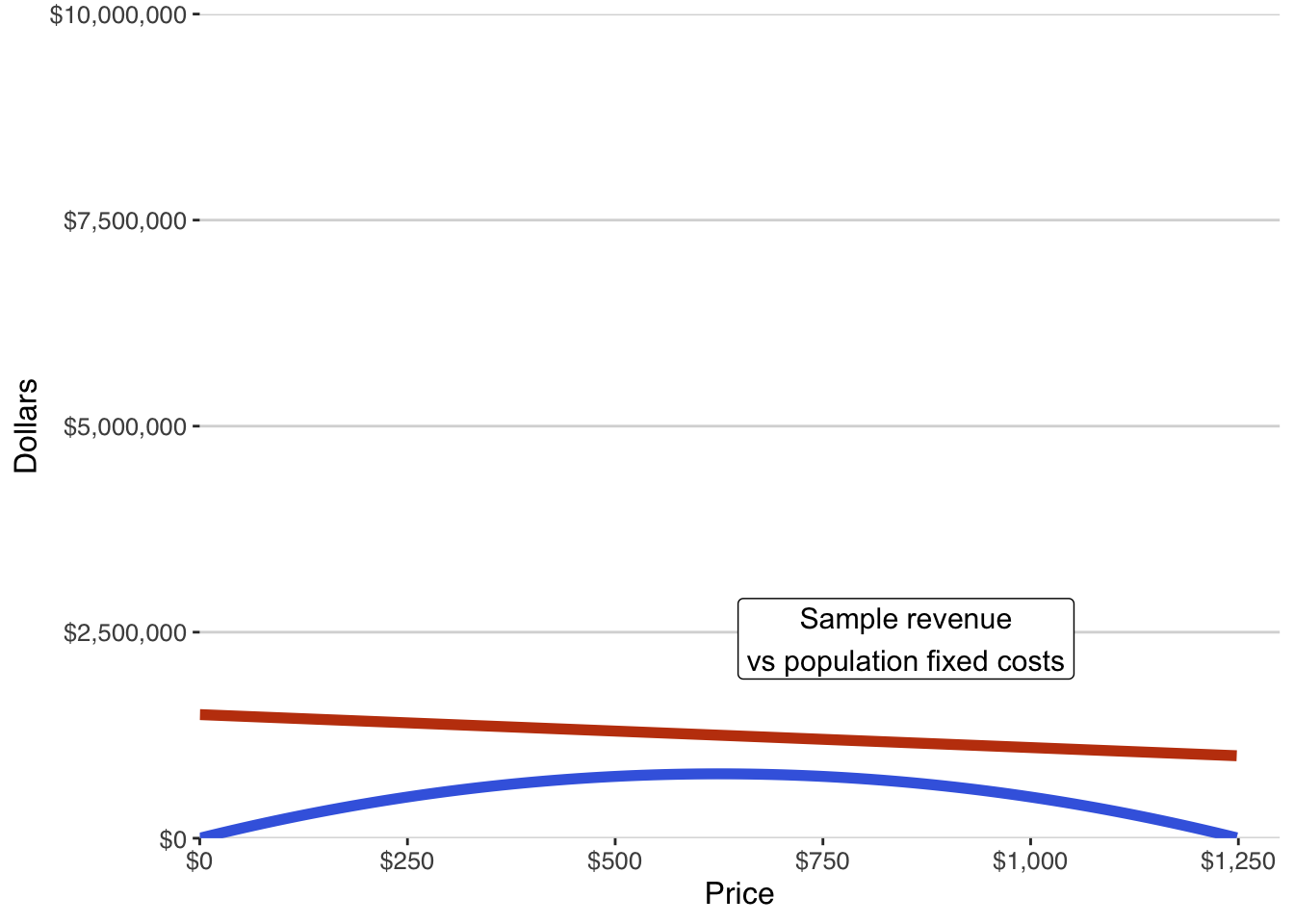

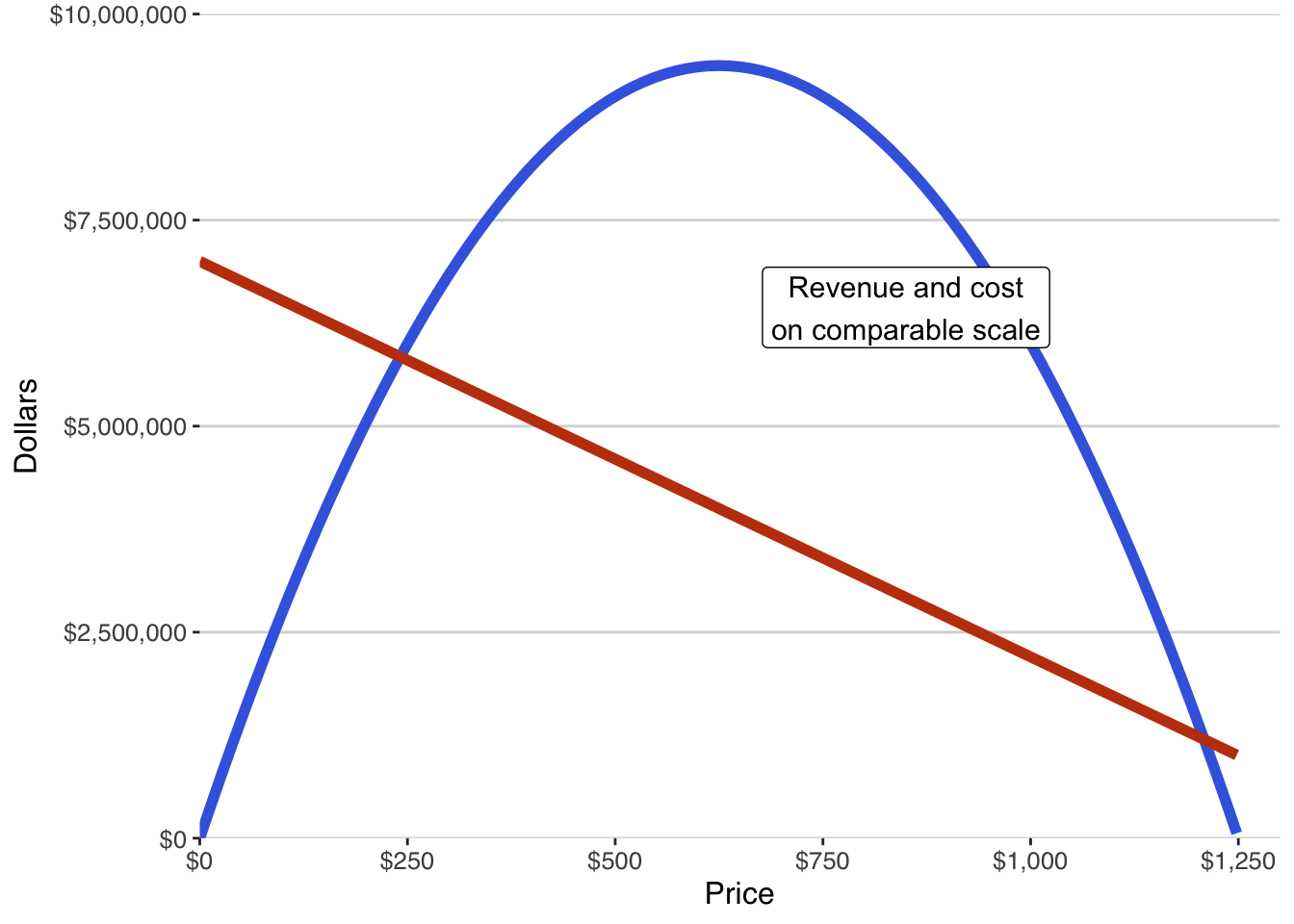

Required Scale Belongs Before Profit Optimization

Only once required scale is understood does it make sense to evaluate profit more formally.

Profit optimization explores how outcomes change across prices and quantities.

Required scale clarifies whether any of those outcomes are worth pursuing at all.

Without this step, optimization risks becoming an exercise in false precision—identifying mathematically optimal outcomes that are structurally implausible.

With it, optimization becomes what it should be: a tool for stress-testing decisions, not justifying them.

10.5 Bringing Scale Into the Decision

This chapter completes a necessary shift in how the entrepreneurial problem is framed.

Once costs are understood as commitments, demand can no longer remain local. Fixed costs force demand to be aggregated. They require not just willingness to pay, but enough people willing to pay.

That requirement introduces scale.

Scale, however, is not a single idea. It emerges from several distinct constraints:

- population limits how much demand can ever exist,

- access limits how much of that population can be reached,

- and penetration determines how much demand must materialize to support fixed commitments.

None of these quantities are forecasts. They are conditions.

Together, they define whether the venture can plausibly support the cost structure being considered. If those conditions are fragile—dependent on optimistic assumptions about reach, adoption, or timing—that fragility is part of the decision and should be acknowledged explicitly.

At this point, the problem is no longer abstract.

We know:

- how customers respond to price,

- what it costs to serve them,

- what commitments are required to proceed,

- and how much scaled demand would be needed for those commitments to make sense.

What remains is to bring these elements together.

That is the role of profit.

Profit is where demand, cost, scale, and commitment meet. It is where feasibility becomes explicit, tradeoffs become visible, and the original question—“Is this worth doing?”—can finally be answered in a disciplined way.

The next chapter turns to that question directly.