12 Profit Reasoning

Seeing the Pre-Revenue Decision Clearly

In the previous chapter, profit was treated as a decision object.

This chapter treats it as something that can be reasoned about.

The goal is to make the implications of the decision visible enough to judge deliberately.

This is where analytics enters the picture most directly.

What This Chapter Is (and Is Not)

This chapter is about interpretation, not execution.

It does not teach statistics.

It does not teach optimization techniques.

It does not teach software interfaces.

Those tasks are handled by tools.

What this chapter does is show how profit reasoning:

- reveals feasibility,

- exposes fragility,

- and clarifies tradeoffs.

The app supports this process by translating demand, cost, and scale into visual and comparable forms. It does not decide. It does not validate. It does not replace judgment.

Why Seeing Profit Matters

Up to this point, much of the analysis has been abstract.

We have talked about:

- demand curves,

- cost structures,

- population constraints,

- and conditional expectations.

Profit reasoning brings these elements together in a way that can be seen.

Seeing matters.

A single number can obscure fragility.

A verbal description can understate tradeoffs.

A profit curve makes structure visible.

It shows:

- whether profit is even possible,

- where it becomes possible,

- how sensitive it is to assumptions,

- and how quickly it deteriorates when those assumptions are violated.

This is not about finding “the answer.”

It is about understanding the shape of the decision.

Profit Curves Are Maps, Not Targets

A profit curve shows profit as a function of price.

That framing is deliberate.

Throughout this book, price has been treated as a choice variable. Demand responds to price. Costs are incurred to support prices. Scale requirements emerge from price–quantity relationships.

A profit curve makes those dependencies explicit.

But a profit curve is not an instruction.

It does not tell you what price to choose.

It does not remove uncertainty.

Like all maps, it is a simplification.

And like all useful maps, it is meant to be interpreted.

The Role of the Profit Analytics App

The profit analytics app exists to do one thing well:

to make the implications of a decision legible.

It:

- rescales demand appropriately,

- incorporates cost commitments,

- and computes profit across prices consistently.

What it does not do is decide whether the venture is worth pursuing.

That responsibility remains with the entrepreneur.

The sections that follow explain how to read profit curves, how to recognize fragile decisions, and how to use sensitivity and robustness to guide judgment—without pretending that uncertainty can be eliminated.

12.1 When Profit Is Impossible

One of the most common—and most unsettling—results entrepreneurs encounter is a profit curve that is negative everywhere.

No matter the price, profit never crosses zero.

This outcome is easy to misinterpret. It often triggers a rush to fix something: adjust the model, revisit the data, or search for a better price. But before reacting, it is important to understand what this result actually means.

A profit curve that is everywhere negative is not a failure of analytics.

It is a diagnosis.

What “Impossible” Really Means

When profit is impossible, the analysis is saying something very specific:

Given the current assumptions about demand, cost, and scale, there is no price at which the venture can support its commitments.

This is not a claim about the future.

It is not a prediction of failure.

It is a statement about feasibility under the current design.

That distinction matters.

Profit impossibility is not a verdict on the idea. It is a signal that something structural must change for the decision to make sense.

The Three Most Common Causes

When profit is negative everywhere, the cause almost always lies in one of three places.

First, demand may be too weak at feasible prices.

Customers may be price-sensitive, the willingness to pay may be low, or demand may fall off too quickly as price rises.

Second, costs may be too high relative to demand.

Variable costs may leave too little contribution, or fixed costs may be too large for the scale that demand can plausibly support.

Third, scale may be misaligned.

Demand may have been learned correctly at the sample level, but the accessible population may be too small—or the penetration required too high—to carry the commitments being assumed.

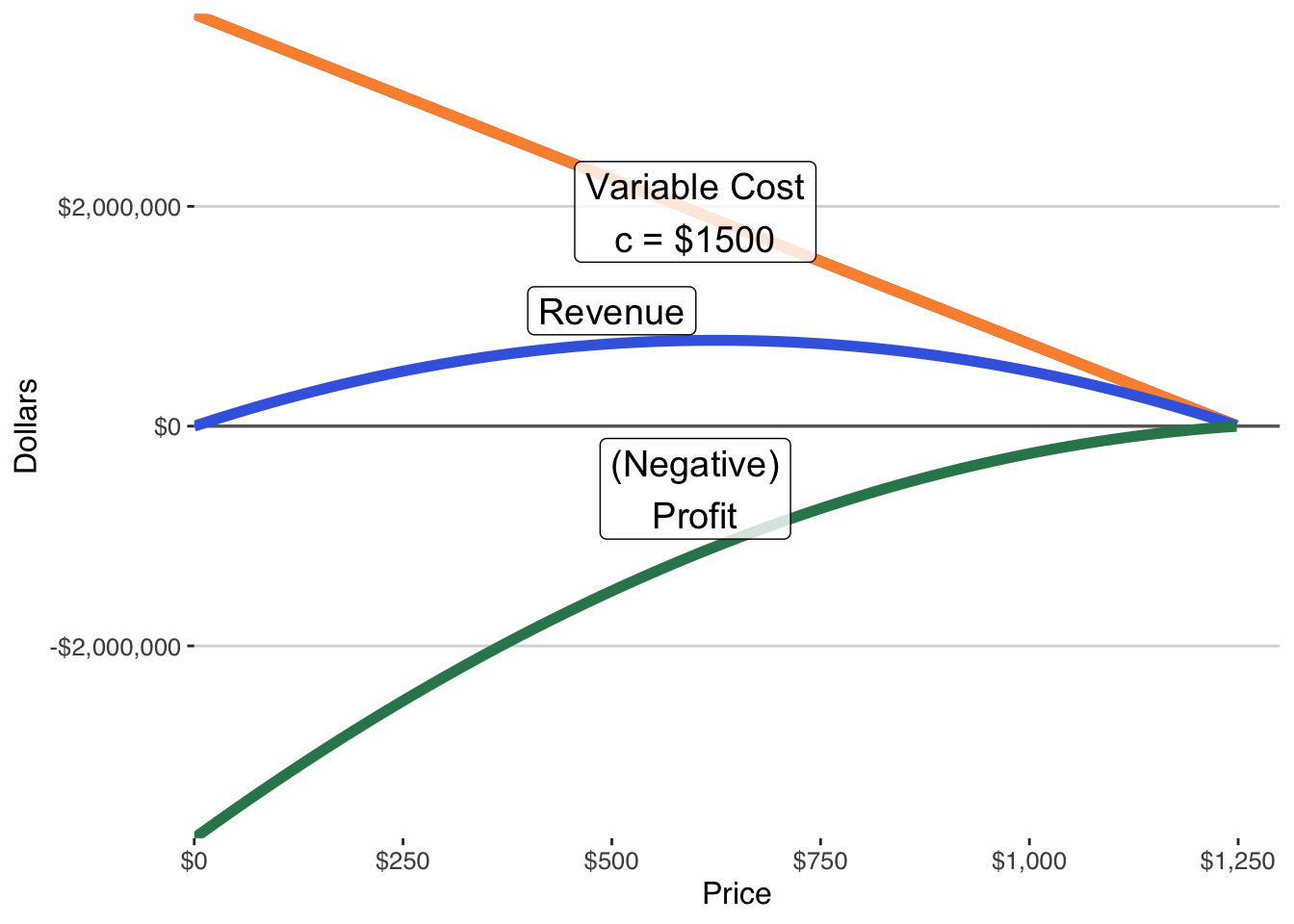

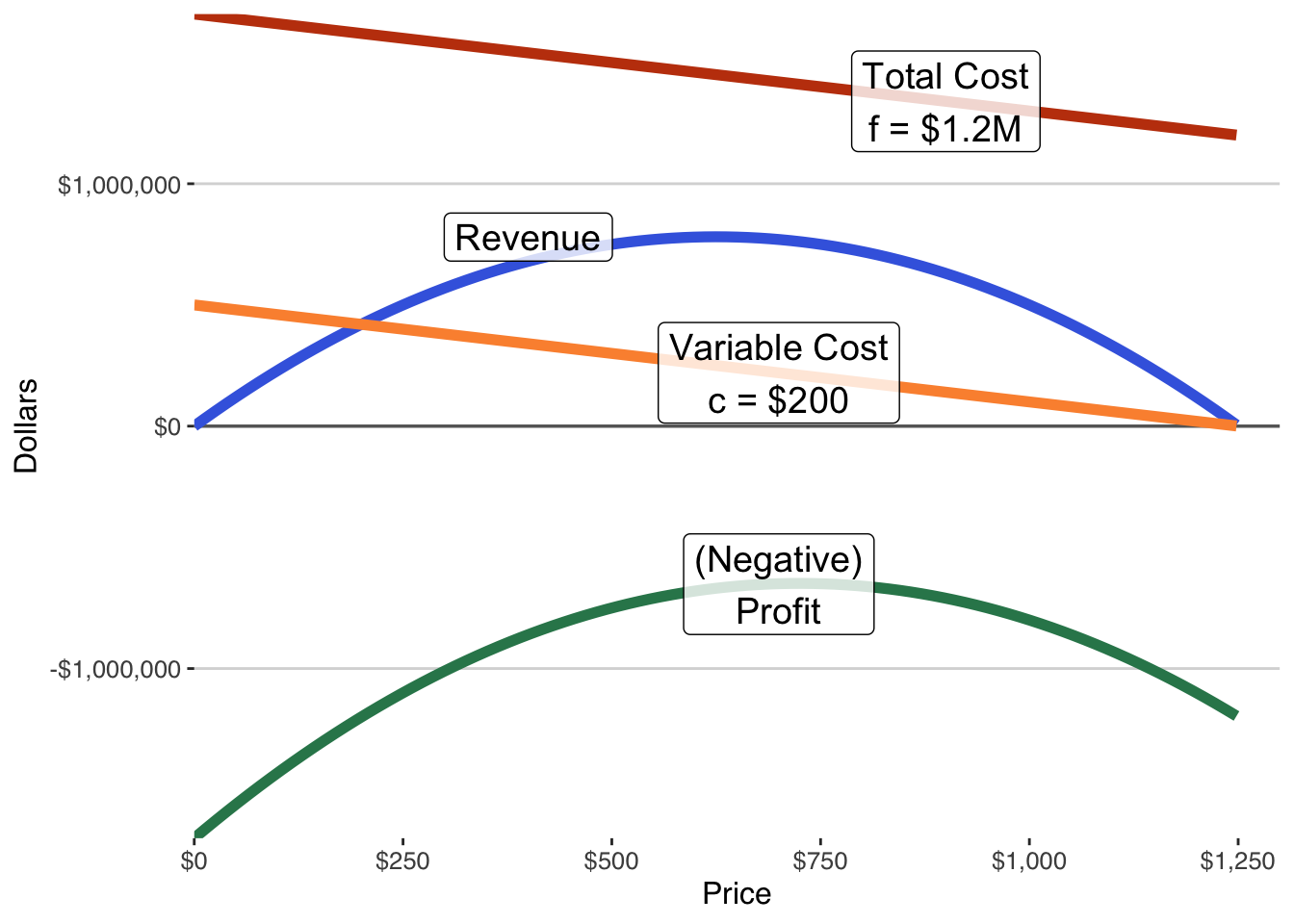

It is worth noting how the three common causes of impossible profit appear in the figures below.

“Weak demand” never appears on its own. It only matters insofar as it fails to clear variable costs or fails to scale enough to support fixed commitments. In other words, weak demand shows up through margins or through scale—not as a separate case.

Each of these causes points to a different kind of response.

Why This Result Is Often a Gift

It is tempting to view impossible profit as discouraging.

In reality, it is often one of the most valuable outcomes analytics can deliver.

It prevents entrepreneurs from:

- mistaking activity for viability,

- committing to cost structures that cannot be supported,

- or relying on growth narratives that never reconcile with economics.

Seeing that profit is impossible before making irreversible commitments is exactly the kind of uncertainty reduction this book has been advocating.

What Not to Do Next

When faced with impossible profit, there are a few reflexive responses that are rarely helpful.

Do not:

- treat the result as a prediction that the venture will fail,

- assume the model must be wrong simply because it is inconvenient,

- or search for a single “fix” that magically restores feasibility.

Profit impossibility is rarely resolved by tweaking one number. It reflects a misalignment among demand, cost, and scale.

Understanding that misalignment comes before attempting to change it.

What This Result Actually Invites

An impossible profit curve invites questions, not conclusions.

It asks:

- Which assumption is doing the most damage?

- What would need to change for profit to become possible?

- Are those changes within our control—or even desirable?

Sometimes the answer is to redesign the offering.

Sometimes it is to delay fixed commitments.

Sometimes it is to redefine the target population.

And sometimes it is to stop.

None of those responses are failures. They are disciplined outcomes.

Impossible profit is only one of the outcomes profit reasoning can reveal.

In many cases, profit is not impossible—it is merely fragile.

In those situations, the profit curve does cross zero. There is at least one price at which the venture appears viable. But that apparent viability often depends on a narrow range of assumptions, precise execution, or optimistic beliefs about scale and access.

These cases are more subtle—and often more dangerous—than outright impossibility.

The next section examines what it means when profit exists, but only barely.

12.2 When Profit Exists but Is Fragile

In many cases, profit is not impossible.

The profit curve crosses zero. There is at least one price at which the venture appears viable.

At first glance, this feels encouraging. After the stark clarity of impossible profit, fragile profitability can look like progress. But this reaction is often mistaken.

Fragile profit is not a relief from judgment.

It is an invitation to deeper judgment.

What Fragile Profit Looks Like

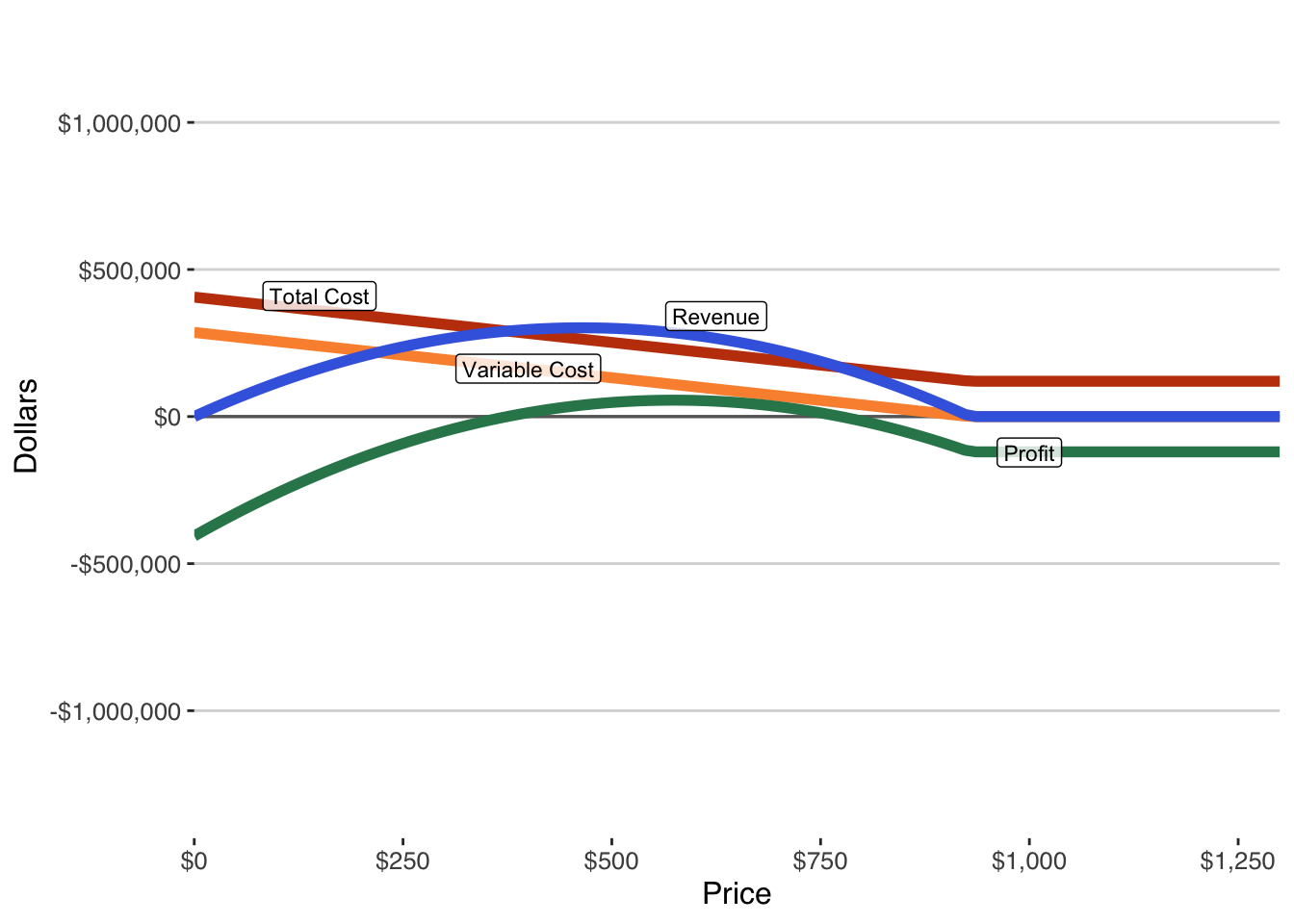

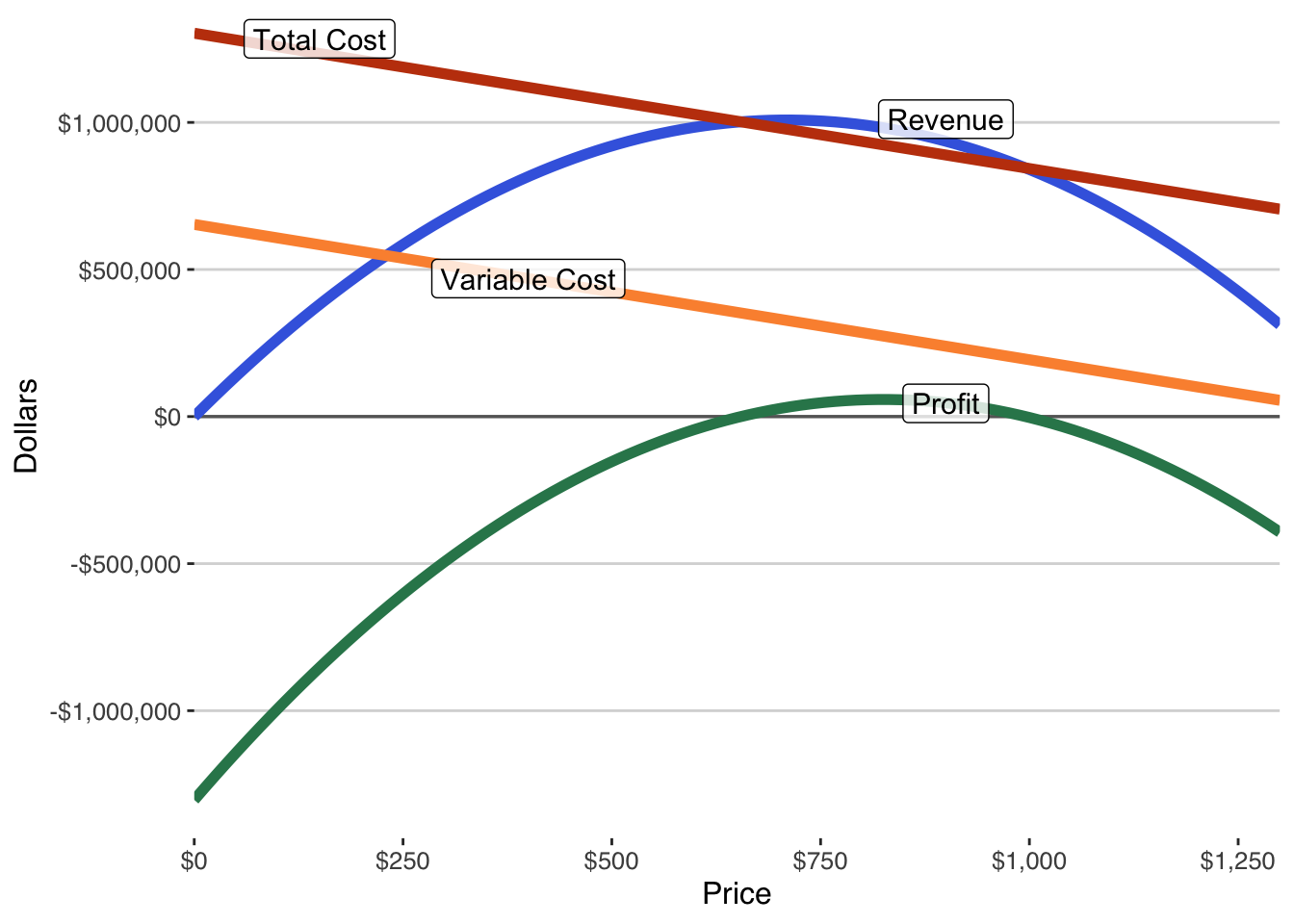

Fragile profit usually appears in one of two ways.

In some cases, profit is positive only over a very narrow range of prices. A small deviation—caused by competitive pressure, execution error, or misestimated demand—pushes profit back below zero.

In other cases, profit is technically positive but very small relative to the commitments required. The venture survives on paper, but only barely, leaving little room for error or learning.

The figures below show these two forms of fragile profit.

In the first, costs are relatively low, but demand is thin. Profit exists, but only within a narrow range of prices and assumptions.

In the second, demand is strong, but fixed commitments are large. Contribution is real, yet the scale required to justify those commitments leaves little room for error.

In both cases, the curve sends the same message: The decision works only if many things go right at once.

The question is not whether the peak is positive. It’s whether the decision survives being a little wrong.

Why Fragile Profit Is Often More Dangerous Than Impossible Profit

Impossible profit is clear.

It tells you that the current design does not work. The decision must change—or stop.

Fragile profit is ambiguous.

It offers a plausible story of success while quietly amplifying risk. Because profit exists somewhere, it becomes tempting to focus on finding and defending that point rather than questioning whether the underlying structure is robust enough to support commitment.

This is where entrepreneurs are most likely to overinterpret analytics.

A single positive region on the profit curve can be mistaken for validation. In reality, it may represent little more than a knife-edge condition.

Fragility Is About Sensitivity, Not Sign

The key distinction in this section is not whether profit is positive or negative.

It is how sensitive profit is to error.

When profit is fragile:

- small changes in demand assumptions matter a great deal,

- small cost overruns erase surplus,

- small shortfalls in scale undermine feasibility.

None of these errors are unusual. All are common in early ventures.

Fragile profit does not fail because entrepreneurs are careless.

It fails because uncertainty is unavoidable.

The Temptation to Optimize Too Early

Fragile profit often triggers an instinct to optimize.

If profit is positive at one price, why not fine-tune the model to find the best one?

This instinct is understandable—and premature.

Optimization sharpens the knife’s edge. It does not widen it.

Before worrying about where profit is maximized, the more important question is whether profit exists over a wide enough range of assumptions to justify commitment.

That question is about robustness, not optimization.

What Fragile Profit Actually Invites

When profit exists but is fragile, the analysis is not telling you to proceed.

It is asking you to reflect.

It asks:

- Which assumptions must hold exactly for this to work?

- How much error can we tolerate before the decision fails?

- Are we willing to accept that level of exposure?

Sometimes fragile profit can be strengthened:

- by delaying fixed commitments,

- by redesigning cost structure,

- by narrowing focus to a more accessible population.

Other times, fragility is a warning that the venture is too exposed to proceed responsibly.

Profit reasoning does not answer these questions.

It makes them unavoidable.

The next section shows how sensitivity and robustness help identify which assumptions deserve the most attention before a decision is made.

12.3 Sensitivity and Robustness

Once profit exists—but only narrowly—the decision shifts again.

The question is no longer whether profit is possible.

It is how easily that possibility disappears.

This is where sensitivity and robustness matter.

Sensitivity Is About Fragile Assumptions

Sensitivity asks a simple question: Which assumptions, if wrong, would reverse the decision?

Every profit estimate rests on assumptions:

- about demand shape,

- about willingness to pay,

- about costs,

- about scale and access.

Sensitivity analysis examines how profit responds when those assumptions change.

If a small change in one assumption causes profit to vanish, the decision is highly sensitive to that belief. If profit remains positive across a wide range of plausible values, the decision is less sensitive.

Importantly, sensitivity is not about likelihood.

It is about consequence.

An assumption can be unlikely to be wrong and still dangerous if being wrong would be catastrophic.

Robustness Is About Decision Survivability

Robustness takes a broader view.

Rather than asking whether profit is maximized at a particular point, robustness asks: Does this decision survive reasonable error?

A robust decision is one that remains acceptable even when:

- demand is weaker than expected,

- costs run higher than planned,

- adoption is slower than hoped,

- or execution is imperfect.

Robustness does not require certainty. It requires resilience.

This is why robust profit often matters more than maximal profit. A slightly lower expected profit that survives error can dominate a higher expected profit that fails under mild deviation.

Why “Most Sensitive” Is Not Always “Most Important”

Sensitivity analysis often produces rankings: which variable matters most.

These rankings are easy to misread.

An assumption can be highly sensitive but largely uncontrollable. Another can be moderately sensitive but actionable. Treating all sensitivity equally can lead entrepreneurs to focus on the wrong risks.

What matters is not just how much profit changes, but:

- whether the assumption can be tested further,

- whether it can be influenced by design,

- and whether it can be insured, delayed, or avoided.

Sensitivity reveals exposure. Judgment decides response.

What the Analytics Is Actually Doing Here

At this stage, analytics is not predicting outcomes.

It is mapping fragility.

By varying one assumption at a time and observing how profit responds, the analysis shows:

- where the knife’s edge lies,

- how wide the margin for error is,

- and which beliefs deserve the most scrutiny before committing.

The app helps by making these relationships visible. It does not tell you which assumptions are true. It shows you which ones matter.

That distinction is critical.

Sensitivity as a Guide for Learning, Not Optimization

One of the most valuable uses of sensitivity analysis is deciding what to learn next.

Highly sensitive assumptions are prime candidates for:

- additional experimentation,

- targeted data collection,

- staged commitment.

Low-sensitivity assumptions, even if uncertain, may not warrant further effort.

This reframes learning as a strategic choice. Time and attention are scarce. Sensitivity helps allocate them.

Robustness and the Willingness to Commit

Ultimately, sensitivity and robustness return the analysis to its original purpose.

The decision is not:

- “What is the best price?”

- “What is the highest expected profit?”

The decision is: Am I willing to commit resources to this design, given how fragile or robust it appears to be?

Analytics can clarify that tradeoff. It cannot resolve it.

Choosing to proceed with a fragile opportunity may still be rational—but only if the risk is understood and accepted. Choosing to wait, redesign, or walk away may be equally rational.

Sensitivity and robustness do not eliminate judgment.

They discipline it.

The final section of this chapter brings these ideas together and shows how profit reasoning supports—not replaces—the decision to commit.

12.4 Is This Worth Doing?

By this point, the analysis has done everything it can.

Demand has been learned as evidence, not assumed.

Costs have been treated as design choices and commitments.

Scale has been made explicit rather than imagined.

Profit has been examined for feasibility, fragility, and robustness.

What remains is not an analytical problem.

It is a judgment.

What This Decision Is—and Is Not

The question “Is this worth doing?” is often misunderstood.

It is not:

- a prediction of success,

- a claim about future dominance,

- or a guarantee of profit.

It is a disciplined assessment of whether the structure of the opportunity plausibly justifies commitment before revenue exists.

This is why profit reasoning matters here. It forces that assessment to be explicit.

The Core Question, Made Precise

At this stage, the entrepreneurial question can be stated clearly: Given what we know about demand, cost, and scale, is there a plausible path to profit that survives reasonable error—and are we willing to commit to it?

Notice what this question does not ask:

- It does not ask for certainty.

- It does not ask for maximization.

- It does not ask whether the idea is exciting.

It asks whether the economics are strong enough to justify moving from exploration to commitment.

How Profit Reasoning Supports the Call

Profit reasoning does not tell you what to do.

What it does is narrow the space of responsible choices.

It makes clear:

- when profit is impossible and the design must change,

- when profit exists but is too fragile to justify commitment,

- and when profit appears robust enough to proceed deliberately.

This clarity is valuable even when the answer is “not yet” or “not like this.”

Avoiding premature commitment is not failure. It is good decision-making.

Commitment Is the Real Irreversibility

Up to this point, most decisions have been reversible:

- prices can change,

- experiments can be rerun,

- designs can be adjusted.

What makes this decision different is commitment.

Fixed costs, infrastructure, hiring, and scale introduce irreversibility. They convert uncertainty into exposure.

This is why the profit question must be answered before those commitments are made—not after.

Profit reasoning helps ensure that when commitment happens, it is intentional rather than accidental.

Acting Without Illusion

Choosing to proceed does not mean uncertainty disappears.

Demand may disappoint.

Costs may rise.

Scale may be slower than hoped.

The goal of profit reasoning is not to eliminate these risks. It is to ensure that they are understood and accepted rather than ignored.

Likewise, choosing not to proceed is not a rejection of entrepreneurship. It is often a sign that learning has done its job.

What Comes Next

If the decision is to proceed, the next phase looks different:

- profit assumptions become hypotheses,

- sensitivity points become monitoring priorities,

- and robustness becomes an ongoing concern rather than a one-time test.

If the decision is to wait, redesign, or stop, the analysis has still succeeded. It has prevented commitment to a structure that could not plausibly support it.

In either case, the question “Is this worth doing?” has been answered more honestly than intuition alone would allow.

That is the contribution of profit analytics at this stage—not certainty, but clarity.